“It feels more real than the other activities we do”: community-engaged storytelling with youths in the United States

5 October 2023

By Joanna A. Tzenis

I am not a traditional scholar. As University of Minnesota Extension faculty, my role is to translate research into practical educational programs to address critical community needs and to study the impact of these programs. I chose research methods that directly contribute to youth and their communities flourishing. Storytelling methods have been the perfect fit for my current project, “4-H Portraits of Home”, a youth program designed to help youth develop trust and empathy with those they feel are different from them.

This storytelling project is a direct response to a critical issue in rural Minnesota communities, and rural communities nationwide. The POH team (an interdisciplinary team of scholars, educators, and community members) conducted a needs assessment that revealed that Minnesota rural communities were experiencing increased and contentious social and racial divisions. Racist acts in these communities made the news. On a national level, in the United States, youth isolation has been named a national priority, as the pandemic, the political climate, and the nation’s racial reckoning has severed social connections and exacerbated historical inequities. This pointed to a need and a community desire to build a culture of connection, trust, and empathy across differences.

Building a youth program

In response to these community needs, the Portraits of Home youth program was built. This program is designed to be a space for youth to share their community experiences freely and safely, reimagine a better world, and empower them to enact social change.

We designed a program that supports youth-driven exploration of diverse histories, narratives, and worldviews through storytelling. The objectives of the program are for youth to:

- develop greater empathy and understanding of those they feel are different from them

- develop trust and build positive intercultural relationships with individuals and community

- be valued and respected by others across cultural lines

- share power around issues of common concern.

The deliberate choice to use storytelling methods in this collaboration was never driven by my or team members’ personal or scholarly interests in storytelling. Instead, as we gained a deeper understanding of both the community needs and examined the literature around arts-based methods, storytelling emerged as the most effective pedagogical approach to support youth in critically reflecting on their experiences with community belonging.

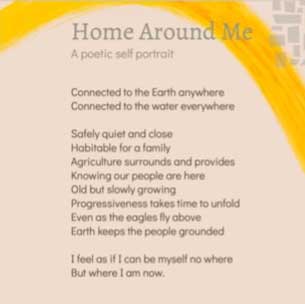

For this project, research and program design were one and the same. For example, we incorporated a mask-making activity in our approach, which was adapted from a youth curriculum to support Social Emotional Learning (SEL) development. Youth also engaged in a photovoice activity where they used photography to document spaces of belonging in their community, they interviewed community members, wrote poems, and engaged in a “sound walk” where they narrated their emotions and thoughts in community spaces and then a peer retraced their steps listening to the recorded narration. They used these artifacts to create a final, digital story about their diverse experiences of belonging in their community. The project team wrote field notes after each program meeting, collected the youths’ artifacts/creations, and interviewed youth participants after the conclusion of the program. Participants represented the changing demographics of the communities in which they live.

“It feels more real”

The storytelling’s strength is how it encourages authentic youth participation. I saw this happen quite clearly, for example, in the mask-making activity that we used to help young people explore their identities with peers they did not know. For this activity, youth interviewed a peer and decorated the outside of a mask with what they believed represented their peer. Then, each youth decorated the inside of their own mask to express their authentic selves. I watched young people decorate the inside of their masks. They worked so intently. Quietly. Without filters. Then, when given the opportunity to engage in verbal dialogue about their masks, youth were not obligated to muster up courage and locate the words to share vulnerabilities aloud. They could simply point to their mask and describe what they had created. As one youth later reflected, “It feels more real than the other activities we do.”

Young people tell the story of parts of their identity that they conceal from others by decorating the inside of a mask.

We also saw that young acquired new tools to express emotions throughout the program. For example, the word “mask” slowly and perhaps subconsciously was embedded in the young people’s vocabulary as they continued sharing stories of belonging in their communities.

A youth participant depicted how a new student likely feels obliged to "put on a mask until there is a comfortable feeling."

Storytelling, therefore, improves the quality of research in addition to supporting youth access and expressing hidden emotions and elicit authentic responses. More traditional methods might have elicited youth to share experiences drenched in self-preservation and deference to perceived adult expectations.

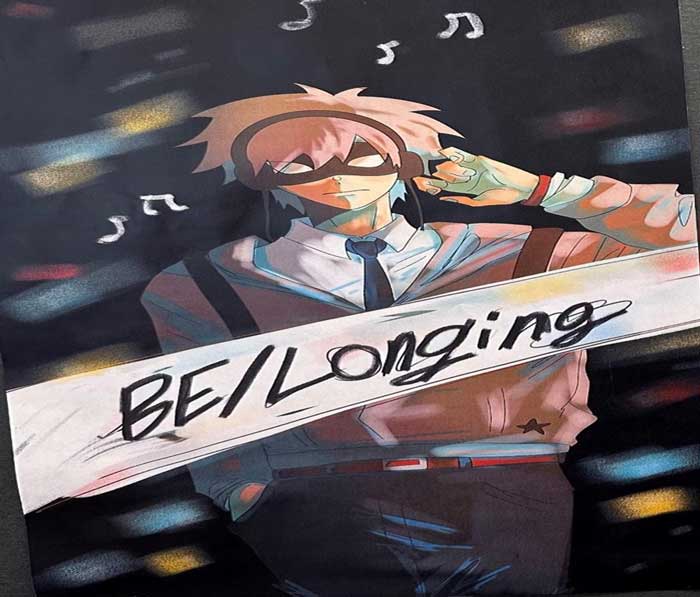

“The communication was through the art.”

The storytelling activities helped young people locate their feelings and express them meaningfully to others. This in turn, allowed their peers to gain a deeper understanding of their lives and community experiences. A highlight of this project was seeing youth who rarely spoke assert their voice through storytelling. As part of one young girl's storytelling project, she captioned her art saying, “I don’t really know how to communicate with others well. But I found . . .that…the communication was through the art.”

One way this young person was able to share her experiences with belonging was through interviewing her cousin about her immigration story from Cambodia to this new rural, US community. To share her cousin’s story, she drew a photo of her cousin assuring her younger self that life would get easier. When reflecting with me and another team member, this young girl started to connect this to her own immigration story, showing evidence that she was gaining a better understanding of herself. She struggled to find words again, but accessed her emotions: “they wanted a better chance to raise their kid and for a better life. I'm gonna cry. Oh, my God.”

To depict her cousin's immigration experience, a participant drew her cousin assuring her younger self that everything will be okay.

What’s next

Our priority going forward is to build our program model to scale. It is important that we take what we have learned, improve the program design, and then work to ensure that this youth storytelling program is sustained within Extension’s organizational structures. We are certainly analyzing the data and hoping to publish what we have learned, but to the team, what matters most is community impact. We care that the program continues to help youth connect across differences and imagine improved and more inclusive communities.

Joanna Tzenis (PhD) is faculty member at the University of Minnesota Extension department of Youth Development. The POH project is a collaboration between the University of Minnesota College of Education and Human Development's Department of Organizational Leadership, Policy, and Development, the University of Minnesota Extension's Department of Youth Development, and the Minnesota 4-H program. It is supported by funding from the UMN Office for the Vice President of Research and the Laura Jane Musser Foundation. Portrait of Home project team members include: Co-P.I. Dr. Joan DeJaeghere, Co-P.I., Dr. Joanna Tzenis, Erma Mujic, Zhuldyz Amankulova, Ashley Purry, Michael Winikoff, Dr. Heidi Fahning, and Sarah Odendahl.

.jpg)