You are here

- Home

- Research

- Impact

- Research Excellence Framework

- The exploitative power of digital food marketing

The exploitative power of digital food marketing

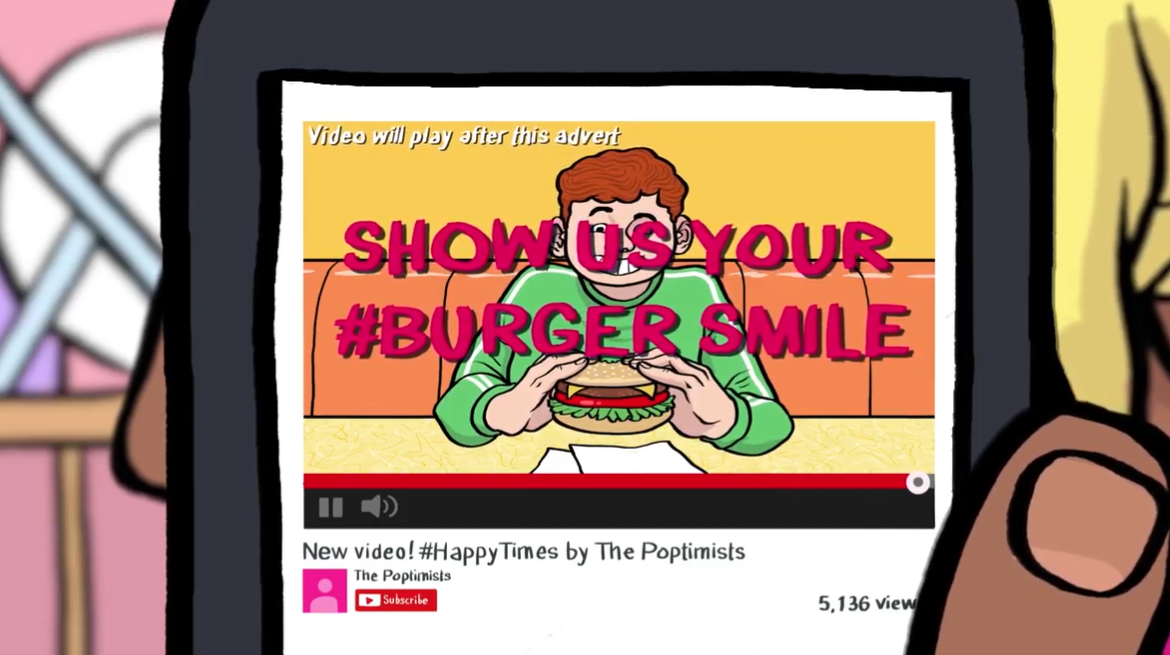

The marketing of unhealthy, highly processed foods influences what children and young people want and what they eat, and we know that this has global consequences for their long-term health and wellbeing.

Digital media platforms have given marketers more power than ever before to target children with ads, including for unhealthy foods, exploiting them and damaging their health. Yet these platforms are closed to researchers and regulators. Mimi Tatlow-Golden’s research into the subject has shaped and informed the policy and legislation of governments, and of non-governmental organisations with a responsibility for public health in Europe, Asia and the Americas, so that policymakers and parents can protect children’s rights to privacy, health and wellbeing.

We know that children spend ever increasing amounts of time online. We also know that they are exposed to marketing that promotes unhealthy foods. But how much do they see, and how much do they engage with it? There is unequivocal evidence that the marketing of unhealthy, highly processed High Fat, Sugar and Salt (HFSS) foods and non-alcoholic beverages contributes to children and young people’s food preferences and eating – and that this links to ill health during childhood and beyond. But much of the evidence that has been generated relates to the effect of TV advertising, not digital marketing, which presents unique challenges to researchers and regulators. We sought to address this knowledge gap to discover the extent of digital marketing’s influence on children, and our conclusion from these findings is that the world cannot allow marketers and brands free rein while leaving it up to children and young people to resist digital food advertising.

We know that children spend ever increasing amounts of time online. We also know that they are exposed to marketing that promotes unhealthy foods. But how much do they see, and how much do they engage with it? There is unequivocal evidence that the marketing of unhealthy, highly processed High Fat, Sugar and Salt (HFSS) foods and non-alcoholic beverages contributes to children and young people’s food preferences and eating – and that this links to ill health during childhood and beyond. But much of the evidence that has been generated relates to the effect of TV advertising, not digital marketing, which presents unique challenges to researchers and regulators. We sought to address this knowledge gap to discover the extent of digital marketing’s influence on children, and our conclusion from these findings is that the world cannot allow marketers and brands free rein while leaving it up to children and young people to resist digital food advertising.

How young people react to digital marketing

We began by conducting some experimental studies to examine young people’s responses to digital food marketing. Through eye-tracking and memory studies of teenagers aged 13 to 17 we could see that young people pay more attention to unhealthy food ads than they do to healthy or non-food ads. We also noted that, after seeing ads in peers’ social media feeds, they recognised and remembered the unhealthy brands that they saw more than the healthy or non-food brands. The studies also showed how digital media marketing weaves itself into young people’s social lives. Young people actually rated peers who had unhealthy food ads in their social media feeds more positively, showing that peer approval was linked to these highly marketed, highly processed foods. They were also more likely to share unhealthy food content that other types of content and become themselves distributors of unhealthy food marketing.

We also conducted a review of the whole digital food marketing ecosystem for the World Health Organization – the first of its kind. This demonstrated to a public health audience how the digital marketing ecosystem works, how children are targeted, and the dangers to children’s rights. The review concluded that existing regulations didn’t address many of the challenges that are presented by marketing in digital media. For example, even though adolescents understand HFSS food advertising and its persuasive intent well, they remain susceptible to it. This is a problem, given the extensive time that teenagers spend on digital media, and the importance of peer networks in their lives.

Furthermore, our review concluded that children of all ages have a right to the protection of their health, to privacy and to not be economically exploited. Given international regulations and conventions relating to children’s rights including data protection, we argued that digital marketing breaches children’s rights to be free from exploitation. It is designed to extract personal data from children and attract their attention in order to generate value for digital platforms, marketers and companies, to the detriment of children’s health and rights. We therefore recommended a regulation to incorporate children’s rights.

Putting research into action

Having shone a light on the implications of digital food marketing on children’s wellbeing and their rights, I was keen to put the findings to work through as many channels as possible. To achieve that, I’ve worked as an expert advisor with international non-governmental public health and child rights organisations such as the  World Health Organization and UNICEF; with government agencies; contributed to high level policy workshops, working parties, reports and consultations; and created educative material for parents and educators. I’m glad to say that the research has had a significant impact on public policy, law and services; it has shaped the agenda of public health organisations regarding food marketing to children and helped governmental and non-governmental organisations to generate evidence regarding the impact of food marketing that can change policy and practice.

World Health Organization and UNICEF; with government agencies; contributed to high level policy workshops, working parties, reports and consultations; and created educative material for parents and educators. I’m glad to say that the research has had a significant impact on public policy, law and services; it has shaped the agenda of public health organisations regarding food marketing to children and helped governmental and non-governmental organisations to generate evidence regarding the impact of food marketing that can change policy and practice.

Giving governments and NGOs the facts to inform decisions

To make change, organisations need evidence of the extent and nature of the issue, and that requires structured monitoring of digital marketing of unhealthy food and beverages to children. To provide this, I helped to create the 5-step WHO CLICK Monitoring Framework, an overarching set of principles and approaches to monitoring digital marketing of unhealthy products to children, which can be adapted to different national contexts. I also co-developed a more practical, detailed set of WHO Protocols, embedded within a training toolkit, that offers step-by-step monitoring guidance and support; teaches about marketing, child development and related psychological issues; and provides the tools for countries to generate comparable evidence of the impact of food marketing practices. The toolkit has already been used in Asia, Latin America and countries across Europe to collect data about digital marketing to children.

We also looked at evidence used by consultants to the UK Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) in assessing the impact of digital marketing on children’s health in 2019. We found that this evidence underestimated the scale of marketing and of children’s exposure to it, so much so that a 2020 update of the evidence showed that children and young people were viewing digital marketing twenty times more than the original evidence suggested. We also found that the DCMS and DHSC had underestimated the impact on health that potential online advertising restrictions would have. The government subsequently announced a total online ban of HFSS product advertising due to take effect in 2022.

I have also used the research to make parents and educators more aware of the marketing strategies used to influence children’s thoughts, feelings, ad engagement and eating. I developed an online Open Learn course called ‘Children and young people: Food and food marketing’ which was designed to inform parents and educators of the marketing strategies used to influence children’s emotions and behaviours. This has so far demonstrated the impact of digital marketing on children and young people to over 2,200 parents and educators.

Young people spend a great deal of time online, and they frequently engage with ads that promote unhealthy foods that can affect their eating for life. I and my fellow researchers are determined to help governments make informed decisions that stop children and young people’s digital exploitation and result in healthier lives. Through our research we are providing the evidence that policy makers need to make positive change.

Written by Mimi Tatlow-Golden, Senior Lecturer in Developmental Psychology and Childhood, The Open University.

Research enquiries

For research enquiries email:

WELS-research-admin@open.ac.uk

For student and degree enquiries email:

WELS-student-enquiries@open.ac.uk

Events

Carers Research Group Bi-Annual Conference

Wednesday, June 11, 2025 - 09:30 to 15:30

Walton Hall Campus and Microsoft Teams

Talk 10: Queer(ing) Ageing: Sexual and Gender Diversity in Later Life. Ageing Well Public Talks series 2024/2025

Wednesday, June 11, 2025 - 12:00 to 14:00

Online