Our blog

On this page, you'll find short regular updates written by the project team to explain our progress, focusing on the research methods and emerging findings.

September 2022: Mobile messaging - managing relationships at a distance

Mobile messaging is first and foremost a means of relating to, or connecting with, other people. This means that many anxieties about mobile messaging are really concerns about relationships. Importantly, relationships always involve a balance between, on the one hand, expressing solidarity and connecting with others; and, on the other, maintaining independence, or keeping a distance. This is evident in the way we organise and live our lives but it can also be seen in the way in which we interact with others. When we talk – or sign, or write, or message – we are always working to maintain an appropriate social distance between ourselves and the people we are interacting with. The distance at which we hold people depends on our relationship with them as well as our mood or priorities at the time.

Mobile messaging challenges our need to keep people at an appropriate or comfortable distance because it has the potential to make us available at any time – we are potentially ‘always on’. Our friends know that we keep our phones to hand and they can see when we have read their message. We can control this to some extent – by not opening a message or by turning off the read-receipt function. But we also manage closeness and distance through our interactions; that is, by using language in interaction to construct an appropriate distance between ourselves and our different contacts, while also being careful to maintain our connection with them.

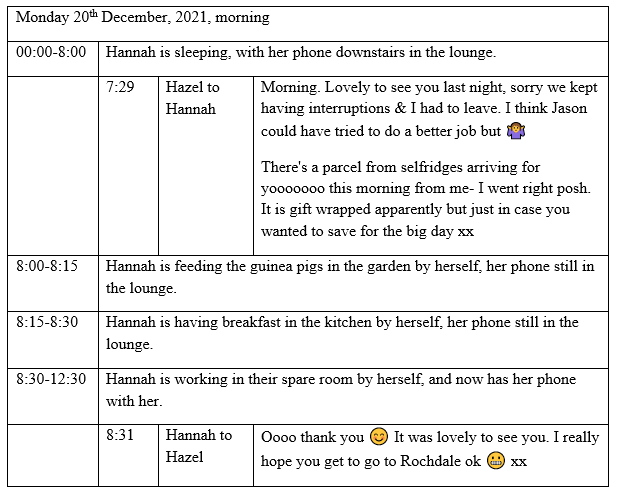

The Mobile Conversations in Context (MoCo) research project explored how this happens in practice. For example, on a Monday morning shortly before Christmas 2021, project participant Hannah receives a message from her old friend Hazel at 7:29am while she is still sleeping. Her phone is downstairs in the lounge, but she is alerted to the message once she is awake by her smartwatch. The table below shows what Hannah is doing and the messages she sends and receives.

When I asked Hannah why she did not reply to Hazel until an hour after receiving Hazel’s message – once she has fed the guinea pigs and had breakfast – Hannah told me she was unusually busy at work and did not want to be distracted by getting into a long chat with Hazel. Not only is her interaction with Hazel shaped by what she is doing at the time – getting ready for a busy work day – but she deliberately delays sending a response as a tactic to avoid initiating a conversation.

If we look more closely at Hannah’s message to Hazel, sent at 8:31 as she settles down to work, we get a sense of how carefully – if subconsciously – Hannah is working to balance connection and distance. Although she has deliberately delayed a reply, her message is nevertheless designed to engage or connect with Hazel. This is evident in the way her language choices echo Hazel’s, suggesting that she’s paying close attention. For example:

- the repetition of ‘o’ in Hannah’s ‘Oooo’ echos Hazel’s own vowel repetition in ‘yoooooooo’;

- Hannah’s phrase ‘It was lovely to see you’ is a reformulation of Hazel’s ‘Lovely to see you last night’;

- and the two kisses (‘xx’) at the end of Hannah’s message also parallel Hazel’s (whilst signalling the end of the exchange).

Hannah also refers explicitly to their shared communicative history, specifically to their Skype chat the evening before when Hazel talked about a planned trip back to their hometown. By paying close attention to Hazel’s wording and their earlier chat, Hannah is showing that she’s aligning with Hazel – she’s maintaining their connection even as she holds Hazel at an appropriate distance.

This balance between connecting and controlling is not unique to mobile messaging – quite the opposite. But the potential intimacy of mobile messaging and the fact that people can contact you at any time bring this tension to the fore. It requires new communication strategies to keep people at an appropriate distance – close, but not so close that it interrupts what you are doing.

We’d love to hear from you if you have any questions or comments about this research update, or on the survey itself, and please get in touch if you’d like to take part. You can email Caroline Tagg (caroline.tagg@open.ac.uk)

July 2022: Attention and rhythm in mobile messaging

For the ‘Mobile Conversations in Context’ (MoCo) project team, whether and how people pay attention is central to their mobile messaging communication. A lot has been written about the ‘attention economy’ – the way that social media companies, businesses and advertisers compete to gain people’s attention in order to boost sales. They do this because otherwise their message or product gets lost in the overwhelming amount of information that circulates on the internet.

Attention is important to our personal online interactions, too. In a world of messaging apps and social media sites, many of us are constantly engaged in multi-tasking – shifting our attention between multiple encounters and activities, both online and offline. Importantly, how we distribute our attention has a social dimension – we have to secure other people’s attention, show that we are paying attention to others, and interpret other people’s displays of attention. Mobile messaging conversations are not only shaped by the other things we are simultaneously attending to, but also by our need to be seen to be paying attention to others.

One way to show you’re paying attention online is through a timely response. Rhythm and pacing are absolutely central to spoken face-to-face conversation – speakers and listeners act like a musical ensemble, sharing the same beat as they respond to each other and take turns. Timing in online interactions is somewhat different, but equally important. Short response times, for example, can suggest intimacy, urgency, approval, presence; delayed replies suggest a lack of engagement or involvement in an exchange. This in turn can (however unwittingly) suggest something about the status of a relationship. Indeed, MoCo survey respondents and interviewees suggest they respond more quickly to people they are closer to: “I usually only respond immediately to my wife”, wrote one survey respondent.

A first look at the MoCo mobile messaging dataset

The MoCo project team set about investigating the above ideas by collecting all the messages sent and received by twelve participants over a three-day period, and exploring them alongside participant diaries. The data suggest that the rhythm of mobile messaging conversations is shaped by what people are paying attention to and how they shift between one focus of attention and another.

Most frequently, people’s use of mobile messaging is part of a real-world task they’re carrying out. To varying degrees, all participants used messaging to do what one research participant, Hannah, called ‘life admin’ – organising activities, parenting, solving problems – most of which involved engaging others in completing a goal. I call this task attending, and it means that the rhythms of often simultaneous mobile conversations are set by the demands of the offline task. Debbie, for example, sets herself the weekend task of sorting out her energy bills, and her request for advice and information leads to various exchanges from multiple contacts. Gabriel contacts his brother and friend to gauge their interest in a trip to Greece, and spends the evening sharing similar bits of information in two intertwining threads.

Most participants find time in their day to ‘check their messages’ when they pick up their phone, read incoming messages and send messages, often to multiple threads. I call this device attending. For example, Alex repeatedly finds time to sit on the sofa, before his children are awake or while they are in the bath, and go through his messages. Eva puts aside some ‘me time’ after putting her son down for a nap, during which she responds to her messages before engaging in prayer. This pattern of engagement involves conversational delays followed by an increase in tempo. Interestingly, these messages are on average longer than other messages, suggesting that people write more when they can do so in their own time.

On other occasions, people pick up their phone in order to share a photo or video they’ve taken. In these cases, people’s attention is less on their device, or even the people they are contacting, but on the world around them, and the rhythm of their online conversation is shaped by that of their offline world. Replies are not expected; and when people do reply, they tend to engage in what’s been called ‘ritual appreciation’, characterised by repeated punctuation (!!!), exclamations and emoji. This is world attending. For example, Phil shares a video of his walk on the beach with his children; Beth shares with her family photos of the origami flowers she and her girlfriend have just made in an online class.

In contrast, only on some occasions do participants engage in what I call focused encounters; that is, real-time conversations to which they appear to be devoting their full attention – and which might most closely resemble face-to-face encounters. For some participants, these stand out from their more typical messaging practices: as Naomi explains, her focused encounter with a bereaved friend is markedly different from her other interactions; she gives her full attention when her friend reaches out to her. Most mobile conversations in the dataset do not end; they simply drop off to be picked up again later. At the end of this focused encounter, however, Naomi takes her leave and explains why she has to go.

Such focused encounters – which we might assume are the norm in spoken, face-to-face conversations – are perhaps the exception to the rule of most mobile conversations.

We’d love to hear from you if you have any questions or comments about this research update, or on the survey itself, and please get in touch if you’d like to take part. You can email Caroline Tagg (caroline.tagg@open.ac.uk)

May 2022: MoCo interviews: “you just don’t want the back and forth”

The Mobile Conversations in Context (MoCo) project explores how mobile messaging exchanges are shaped by people’s everyday lives and offline activities. Mobile messaging is rarely the focus of people's attention but is something that people dip in and out of as they carry out other activities and interactions. As such, WhatsApp messages are not so much turns in a conversation but contributions to a shared space, without the same obligation to respond as in a face-to-face conversation.

The project team interviewed 12 people aged between 35 and 76. The interviewees felt that WhatsApp exchanges could resemble spoken conversations, especially when there is a lot of ‘back and forth’, as Beth (aged 36) put it. But they also recognised ways in which mobile exchanges differ from face-to-face conversations. Mobile exchanges do not necessarily happen in real-time and they can intertwine with each other, not least if ‘you pick up your phone every hour and look at it and reply to anything and put it down again’ (Fran, 53).

What emerged from the interviews is that the pace and rhythm of an exchange is shaped by the extent to which it aligns with or disrupts people’s immediate milieu, or social environment. For example, an exchange is likely to be quicker if it is between people who know each other well and communicate frequently, or where it requires a straightforward answer that doesn't interrupt what people are otherwise doing. Charlie, 40, described friends based abroad:

we’ll have a little sort of catch up and then won’t message for a few weeks ... with them it will tend to be I’ll wait a week or two before I reply ... it’s just a bit more of an effort to write back because it’s like: “what’ve you been doing over the last six months?” ... it’s much easier if it’s someone who I’ve seen recently and they’re just sort of like: “oh did you watch that thing on the telly last night?”

The interviewees acknowledged that they might deliberately slow down the pace of an exchange: ‘I don’t always reply to people immediately, sometimes I’ll delay it because you just don’t want the back and forth’ (Debbie, 53) or ‘it might be that I don’t want them to think that I’m sat there glued to my phone waiting to reply to them’ (Alex, 40). This tactic appears to be widely recognised and understood, in the sense that people acknowledge that their contacts have busy lives and don't necessarily expect them to be available to chat: ‘I don’t care if people reply’, admitted Naomi, 47, ‘I rarely notice’.

Others described mobile messaging as a form of communication for which the back-and-forth of spoken conversation was not necessary – or always desirable. Of a large WhatsApp group comprising neighbours in his road, Ed, 46, said:

What I get grumpy about is when people say things that have already been said or don’t need to be said ... “what number are you?” and they’ll say “200” and they say, “OK, is that all right if I come round now”, “yeah that’s fine”, “okay I’ll see you in a bit”, “great looking forward to seeing you” – it’s, like, we don’t need any of that.

Even in one-to-one chats, as Gabriel, 42, put it:

if you're just shooting the breeze, if you're just sharing memes or whatever, you don't expect a reply to everything, and so conversations can just drop – and then they pick up without so much as a hello a few weeks later: “here's another meme” and that's just a way of maintaining friendships until you see the person face to face.

***

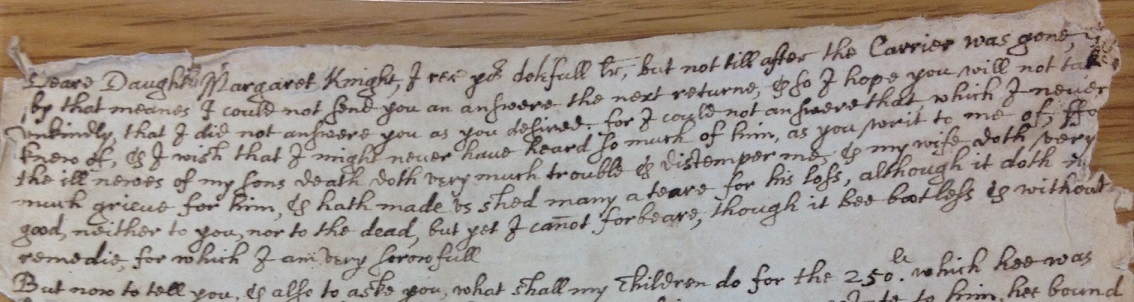

Although mobile messaging thus differs from the instantaneous nature of face-to-face conversation, it has parallels with older forms of written correspondence, such as letters and postcards. Evidence from historical correspondence suggests that writers were aware of expectations around the need to reciprocate. Take, for example, this letter written by William Knight in November, 1649, which starts with an extended apology for a delayed reply:

Dear Daught Margaret Knight, I rec yoɁ dolefull lr, but not till after the Carrier was gone, & so by that means I could not send you an answere the next returne, & so I hope you will not take unkindly, that I did not answere you as you desired, for I could not answere that which I never knew of...

This snippet from the past raises questions about the extent to which conventions surrounding written communication may have shifted over the years as the technologies changed – from letters delivered by couriers to WhatsApp messages sent directly and immediately between mobile phones – and the impact that this may have on how we relate to people and manage our social relationships.

We’d love to hear from you if you have any questions or comments about this research update. You can email Caroline Tagg (caroline.tagg@open.ac.uk)

January 2022: MoCo survey findings – staying connected and in control

Much of what we know about mobile messaging is based on research into young adults in their late teens and twenties. The Mobile in Conversation (MoCo) project survey is important in reaching out to a broader demographic and thus shedding light on how adults of all ages engage with mobile technologies. The 170 survey respondents are mostly UK residents in their mid-30s to mid-50s, in full- or part-time employment, and many have children. Their responses reveal the importance of apps such as Facebook Messenger, SMS and (in particular) WhatsApp for organising life events and maintaining relationships with a range of family, social and work contacts. They also show how mobile conversations are shaped by people’s offline activities and the multiple demands on their time, as well as their beliefs about the place of mobile messaging in their lives.

One key observation from the survey is that people have developed both technological and social strategies for prioritising and managing messages in the context of their busy domestic, social and working lives. Technological strategies included:

- turning off notifications (which 38% of respondents claim to do), so that people are not disturbed and can check messages in their own time. This is done most often for large group chats. In this way, people treat mobile messaging as a sort of noticeboard they can come back to ‘when it suits me’, as one respondent puts it.

- keeping phones on silent (37% respondents), with others explaining that they put their phone on silent at certain times, such as when they are at work, with other people, or sleeping, e.g. ‘Sound all day barring when in work meetings etc. silent all night’. Interestingly, the survey suggests that people who usually keep their phones on silent tend to check their phones more regularly than those whose phones are on sound.

- disabling the functionality that enables other people to see if they are online (22%), mainly to retain privacy and avoid any pressure to reply immediately, e.g. ‘It allows me more time to respond without seeming like I am ignoring or delaying’. Many people who disable this functionality also keep their phone on silent.

Alongside these technological strategies are certain social principles by which people manage their mobile conversations. On the one hand, it appears that people’s use of messaging is shaped by what they are doing at the time. For example, most people claim they frequently or sometimes send messages while watching television (77%) or working (63%), but only 18% say they would do so during lunch with a friend. Some people explicitly cite their belief in prioritising people who are physically present, e.g. ‘Texting while having lunch with a friend is hugely impolite’. Others describe putting their phone away when they do not want to use it or be distracted, e.g. ‘If I’m working or trying to focus on something (e.g. a book) I leave it in the kitchen so it doesn’t distract me’.

On the other hand, when asked what would prompt them to respond immediately to a message, only a few people (18%) put it down to what they are doing at the time. Instead, most suggest that the speed of their reply is determined by how urgent they think the message is (51%), their relationship with the sender (26%) or, sometimes, both: ‘if it’s something urgent, or from my parents’. This challenges the idea that mobile messaging is necessarily a quick and instantaneous way to communicate. Instead, people are clear that they should not always feel under pressure to reply straight away and can do so in their own time.

Respondents also accept that this is true for other people, recognising that a lack of response from a contact might be due to an array of factors, including other activities and priorities. Asked to explain instances in which contacts did not reply (or took their time to do so), 62% cite their contacts’ busy lives: ‘I appreciate that other people have lives of their own!’, writes one respondent.

These strategies and principles seem to suggest that people are attempting to assert control over their communicative practices, or at least want to appear to have this level of control. In particular, they try to resist the social pressure to be constantly available, or ‘always on’. According to the survey, this pressure comes from people’s perception that others expect immediate replies, as well as occasions when messages are sent at inappropriate times or when someone is inundated with ‘pings’ from an overactive group. As shown above, many of the survey responses suggest that people are resisting this pressure: by keeping their phone on silent and turning off notifications, choosing when to engage with mobile messaging apps, and asserting their and others’ right to reply in their own time. Although people may not always do what they claim in a survey, the stances expressed suggest their awareness of the need to push back against social and technological demands and to use technologies in ways which work for them.

We’d love to hear from you if you have any questions or comments about this research update, or on the survey itself, and please get in touch if you’d like to take part. You can email Caroline Tagg (caroline.tagg@open.ac.uk)

October 2021: Mobile conversations in the context of busy lives

Digital technologies such as WhatsApp and other mobile messaging apps are now deeply embedded into many people’s daily lives, both facilitating offline tasks and adding to busy schedules. The following extract describes a fairly typical working day in my life as a middle-aged academic.

Monday 6th September

My alarm goes off at 7am, and my partner and I finally get out of bed at quarter past. As we sit down for breakfast at around half past, I remember to send my twelve-year-old niece a message on one of our family WhatsApp groups: ‘Have a great day back at school!’ (7:29). While we are having breakfast and going for our regular 15-minute morning walk, my niece replies and other family members join in. As I sit down to work at 8am, I respond to a photo sent to the group of my niece in her school uniform: ‘Looking good!’ (8:03). With my phone on silent, I start work by reading some research papers, and at 10:20 move to my computer. At this point I check my phone and find 21 messages sent by my mother and sister to a WhatsApp group the three of us belong to – my mother suspects a problem with her plumbing. Their messages were all sent before 9am, and it’s too late to join in the conversation. I ping off a quick message, expressing my hope that the plumber can come sooner rather than later (10:22), and get back to work. At 12:30, I go for a run, have a shower, and when we sit down to eat lunch at around 13:10, I check my phone to find that my mother and brother are discussing (in a third WhatsApp group) where I should sleep when my mother and I visit my brother in October. I quickly respond – anxious to get a good room – and then continue to check my phone throughout lunch, replying immediately to messages and keeping my partner updated, whether he wants to know or not. I send my last message at 13:43 (‘Yes, that seems fine – I don’t snore!’) before starting work at 13:45, while my brother and mother continue to joke about which of us will need earplugs.

As this diary entry illustrates, mobile messaging interweaves in complex ways with offline activities in many people’s everyday working and social lives. Mobile conversations interrupt physical activities (such as my lunch) and are interrupted by them (my conversations that Monday take place around the edges of my working hours), with implications for our levels of engagement and concentration in both the online and offline spaces. Offline tasks are also facilitated and shaped by mobile conversations, which extend physical activities beyond the immediate offline space and allow us to invite those who are not physically present into the moment. And mobile conversations are in turn shaped by the (multiple) physical environments in which they take place – see, for example, how my contribution to the plumbing conversation was curtailed by my mother’s messages arriving while I was working and not checking my phone. Mobile conversations add another layering to our already busy lifestyles as we move between offline and online spaces and activities – another set of tasks to fit in and additional people to coordinate them with. How can we understand this complex communicative environment and its implications for our social relationships and everyday lives?

Our research project, MoCo (Mobile Conversations in Context), addresses this question by developing an innovative mixed methods approach with a time-use diary – such as the one I carried out during the first week of September – at its heart, accompanied by interactional analysis of the mobile messages sent and received while the diary is being kept. In time-use diaries, people record all their daily activities, where they were and who they were with, making it possible to document what they are doing when they send messages and what is happening around them. The diary is accompanied by in-depth interviews carried out before and after the diary is completed, in which people’s own understandings of their mobile conversations in context can be explored. How typical was the day covered in the diary? What role did each fleeting mobile conversation play in their wider lives? Central to understanding how communication is negotiated and managed as part of busy twenty-first century lives is people’s relationships with others, and this is a key focus of the interviews. In what ways are the rhythm and quality of people’s mobile conversations shaped not only by what they are doing at the time but by who they are messaging and why?

Please keep an eye out for our regular updates on the project’s progress. And do get in touch if you’d like to take part in the project.