Do young people read more books by female or male authors?

Do young people read more books by female or male authors?

One thread of our research project ‘Exploring discourses of representation in Young Adult (YA) fiction (DoRA)’ relates to the fictional worlds that female and male authors construct for their teenage readers.

Initial findings from our computational study of 50 YA books (5 million words) suggests that the sex of authors matters:

female authors tend to use more words connected with emotions and the body, male authors tend to use more words connected with nature and animals.

(For more information on this, see this blogpost)

If girls and boys read a variety of YA books then they’re exposed to all kinds of fictional worlds through the authors they choose to read. But is this the case? Do girls and boys read a variety of authors, or do they have a preference? Our curiosity has led us to take a sneak peek into our survey data, even though the survey is still live [Click here to take part], just to see…..

Are the books you read mainly by female authors or mainly by male authors?

As of December 2025, we’ve had 87 student responses to the survey question (girls n=40; boys n=38, Prefer not to say=3, Describe yourself=6) - ‘Are the books you read mainly by female authors or mainly by male authors?’. With a focus on students who responded as female or male, we found a clear difference between female and male students’ reading habits.

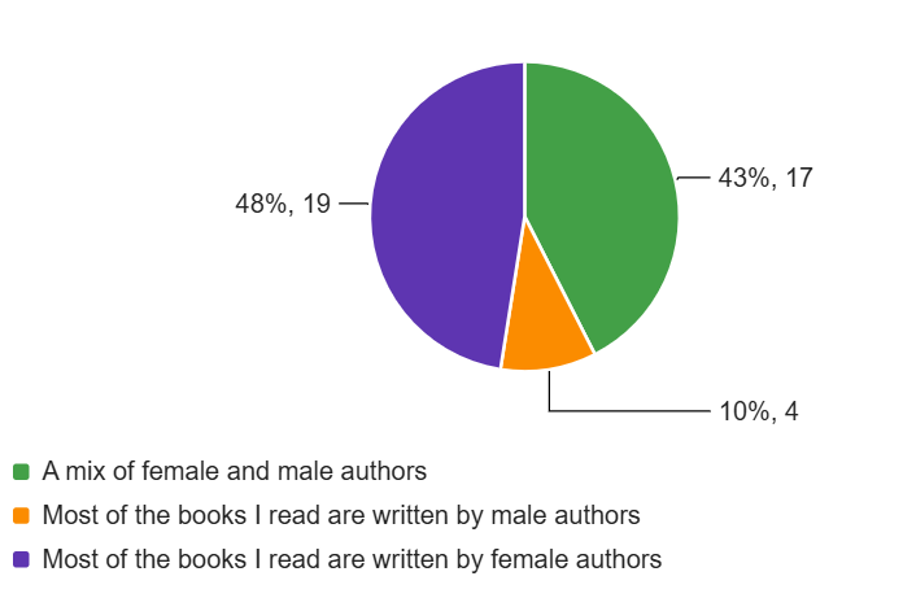

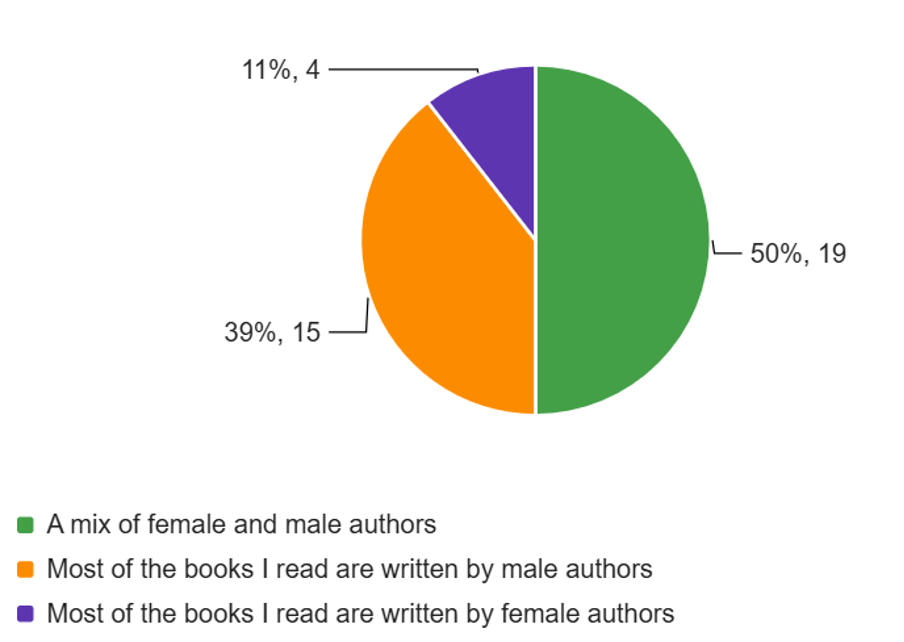

While girls and boys report reading a mix of authors, n=17 and n=19 respectively, roughly the same proportion of students report reading more work by authors of the same sex. Girls (n=19) report reading female-authored works more than male-authored (n=4), while boys (n=15) report reading male-authored titles more than female-authored (n=4) (see Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1: Girls’ responses to ‘Are the books you read mainly by female authors or mainly by male authors?’

Figure 2: Boys’ responses to the question: ‘Are the books you read mainly by female authors or mainly by male authors?’

The survey is still live, and as more students participate, this picture may shift of course. But at the moment, the finding that almost half the survey respondents read books by authors of the same sex, indicates that the impact of different fictional worlds (irrespective of genre) may be worthy of future research.

In the survey, some students also offered their views on what they thought about our research finding that female and male authors construct different fictional worlds. Here are a few of their voices:

I have personally not noticed this difference in my reading - especially classics I have found that there is a balance of emotional behaviours and descriptions between male and female made characters (female student, reports reading a mix of authors)

I haven't noticed this myself but will now be looking out for it! I am not sure if this would affect how young people see the world or act in real life. (female student, reports reading a mix of authors)

because they can impact by putting in the readers head that men don’t care and are not affected by insults or whatever (male student, reports reading more male authors)

I think it's interesting but I also think both of those things are important. Emotions and nature. So it's not really like there is a negative message in either of them. (male student, reports reading a mix of authors)

It could give young readers the idea that women should focus on more intimate, romantic writing and men have to focus on more masculine more atmospheric writing (female student, reports reading more female authors)

It may discourage certain male readers from indulging in female-written fiction if they have been taught, as many young males are, that they are not allowed to show their emotions in the same way as a female (‘Prefer not to say’, reports reading more female authors)

The young people’s views give some insights into their critical skills, their understanding of links between fictional worlds and the real world, and the extent to which students have even considered the idea of gendered fictional worlds in the books they read. Importantly, their voices call for us to understand their views in more depth, particularly if, as we have found here, that girl readers engage with fictional worlds more often connected with emotions, and boy readers embrace those more connected with nature and animals. Might these fictional worlds be taken as a guide for life? This question, remains for the moment unanswered, but it seems to make our explorations of these gendered worlds even more important.

Other survey findings will be shared very soon.