Trials with genre

Crime or thriller? Sci-fi or fantasy? Vampire or paranormal or perhaps romantasy?

Genre of fictional texts is a much-discussed but not widely agreed upon phenomenon, though its utility for both readers and publishers is acknowledged - Thelwall describes book genres as “useful for readers as a device to help them identify books that they may like, and for publishers as a way to help them identify the likely size and nature of a book’s audience.” (Thelwall, 2017, p.3). Often YA fiction is simply classified as... YA fiction, and then a subcategory of another genre. But one person’s Crime genre is another person’s thriller. Is Twilight in the Vampire genre or Romance? What about His Dark Materials? – Fantasy or Action & adventure? And where do emerging categories such as romantasy fit into the mix? (= romance + fantasy in case you were wondering!)

One way we’ve chosen to divide our corpus of 50 YA fiction novels is by author sex – as we’re interested in the extent to which female and male authors write differently. So it was important to us to make sure that any findings resulted from author sex rather than simply the preferred genres of female or male authors. But assigning genre categories to the 50 texts in our collection did not prove to be straightforward.

Publisher descriptions, author blurb and Goodreads

We initially thought we might be able to draw on an existing set of genre categories. And quickly found that this doesn’t exist. We considered adopting genres based on publisher descriptions, author blurb on books, and Goodreads accounts (crowd-sourced data being the way to go) but rejected each of these as they assigned multiple genre labels to each book, rendering any comparison across books impossible.

Genrification

Librarian interviews and our wider reading of practitioner journals pointed to the current trend towards ‘genrification’ of texts in secondary school libraries to increase browsing and discoverability of books. This represents a shift from the more traditional organisation by alphabetical order according to author surname. But when it comes to gentrification, it seems every school adopts slightly different genres. We asked the head librarian in our participating school how she decided on book genres – she said she drew on book catalogues and also consulted others – again, no definitive categorisation.

ChatGPT

Look at the attached list of book titles and authors.

Titles are separated by a semi colon.

These books are all classed as young adult fiction.

Put the book titles into groups based on dominant genres.

Our next step was to ask AI in the form of ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2024), using the above prompt. Again, we thought here we could draw on large amounts of data and gain a broadly-agreed on classification for each text. Each of us separately went through a process of testing and iteratively refining our prompt for ChatGPT as the AI initially omitted some texts. However, comparisons across classifications – both within one researcher’s requests and across researchers’ requests – revealed that ChatGPT responses were slightly altered each time with book titles omitted and genre categories changing. In order to understand the changes, we gave the following prompt:

Write a short description of each genre and justify why each book is in each genre category

But the issue of different responses each time, omitted book titles, and different categorisations necessitated a great deal of cross-checking and meant that ultimately the replies were not very helpful. The lack of stability in the GPT outputs was unsettling, and made the process of assigning genre categories feel extremely ad hoc. (See our presentation in the ‘outputs’ tab on using Chat GPT within our research overall).

Amazon genre labels

Ultimately, we decided to use Amazon’s genre labels as firstly, these were sufficiently narrow (YA then one or two subgenres) and secondly, they’ve been used by other researchers of YA fiction (Cermakova and Farová, 2017; Kraicer and Piper, 2019).

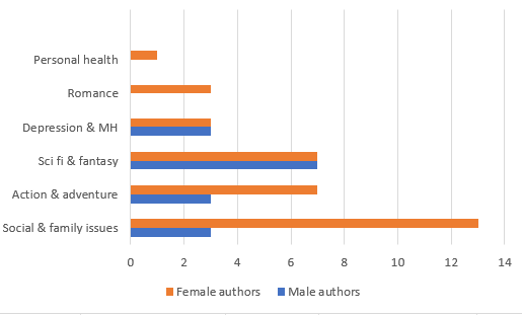

See the figure below for the results of genre labelling for our 50 texts.

Genres of female and male-authored books (raw numbers of books)

The bar chart indicates that both female and male authors’ works in our corpus occur within Depression & mental health, Science fiction & fantasy, Action & adventure, and Social & family issues, though female authors have a far greater proportion of books within the latter (13 books to male authors’ 3 books). Only female authors are classed as Romance, though this is just three books of the 34, and just one book is classed as Personal health.

YA fiction is two-thirds female-authored

So – while a limited sample – our corpus of 50 covers a range of genres for both female- and male-authored works. As with YA fiction generally, our corpus reflects the dominance of female authors (Ramdarshan Bold, 2021) with two-thirds of books in the DoRA corpus written by women. Thirty-four texts are female-authored (comprising 3.6 million words) and 16 are male-authored (1.4 million words). And while women authors of YA are more likely to write about social and family issues than men, both groups cover a range of genres featuring action and fantasy.

If you’ve enjoyed this blogpost, email us to be added to our mailing list for updates to this website: [email protected]

References

Cermakova, A. and Farová, L. (2017) His eyes narrowed — her eyes downcast: contrastive corpus-stylistic analysis of female and male writing. Linguistica Pragensia 27(2):7

Kraicer, E., & Piper, A. (2019). Social characters: The hierarchy of gender in contemporary English-language fiction. Journal of Cultural Analytics, 3(2), 1–28.

OpenAI. (2024). ChatGPT (Version free). https://chat.openai.com

Ramdarshan Bold, M. (2021) ‘The Thirteen Percent Problem: Authors of Colour in the British Young Adult Market, 2017-2019 edition’, International Journal of Young Adult Literature, 2(1), p. 1-35. Available at: https://doi.org/10.24877/IJYAL.37.

Thelwall, M. (2017), Book genre and author gender: Romance>Paranormal-Romance to Autobiography>Memoir. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 68: 1212-1223. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23768